Alice Cooper (and the Muppets) capture an important sentiment: YESSSSSS!!!!!!!!!! The academic year can feel exhausting at the very end, and now that we’ve hit summer there’s a usual, and totally necessary, impulse to celebrate, then relax and unwind. I know I plan to do just that.

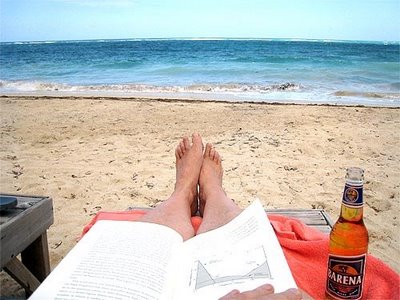

At the same time, summer is also the time when many of us count on the time away from teaching and meetings to get some of our most serious research and writing done. And that’s where we run smack dab into a familiar irony: we can often be our least productive when we have the most unstructured time. Faced both with the perennial “there’s so much… where do I start?” problem and the aforementioned impulse to chillax, we can perceive the expanse of unstructured free time ahead of us, observe, “that’s OK, I’ve got plenty of time,” and then hit the beach, the bookstore, or the Netflix binge.

…and then it’s mid-August, and the next academic year looms. Oops.

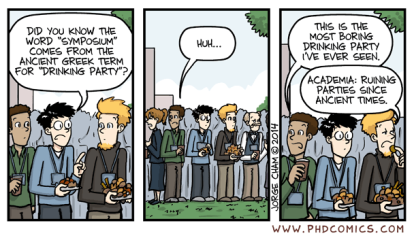

Facing this condition right now (spring grades were turned in yesterday, YESSSSSS!!!!!!!!!!), I happily came across this piece by Indiana University’s Kelly Hanson in Inside Higher Ed‘s GradHacker blog (which is a great resource you should check out, even if your grad student days are behind you). It’s a good reminder of some concrete steps we can take to keep our writing moving forward by adding some structure and intentionality to our summer free time.

__________________________________________________________

Kelly Hanson is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at Indiana University, Bloomington. She loves grad school because even though she gets older, her dissertation just stays the same age. You can follow her on Twitter at@krh121910.

Kelly Hanson is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at Indiana University, Bloomington. She loves grad school because even though she gets older, her dissertation just stays the same age. You can follow her on Twitter at@krh121910.

Summer is upon us here in Southern Indiana, and in between barbeques and long weekend bike rides, I have some epic plans for my dissertation this summer. The trouble? The lack of semesterly structure makes me feel like I am untethered. Summer, for me, is one of the most difficult times to write. My summer productivity has been hit or miss in the past. But this summer, I am ready to get this chapter done.

During the semester, I have found the most effective way to get writing done is to create a daily schedule with scheduled and measurable goals. In the summer, this is even more important for me because when my schedule is so open I feel like I can just always write later. Creating a summer calendar to match my goals is the only way I can get writing done during the summer. We’ve written before about the transition between summer and the semester, but today, I offer some techniques for transferring your writing projects from the regimented time of the semester to the amorphous and unscheduled expanses of summer break.