In Reflective Teaching and Learning, Jennifer Harrison explains the roots of “reflective practice” in John Dewey’s examination of though and problem solving in the classic 1910 volume How We Think: “Dewey’s view was that reflective action stems from the need to solve a problem and involves ‘the active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it’” (Harrison 9, citation omitted). Harrison continues to explain that reflective practice can be considered as occurring at three levels, each succeeding level being less instinctual than the previous:

- technical reflection: examining events and action to determine what worked and what didn’t, and why;

- practical reflection: examining “the interpretative assumptions you are making in your work” (Harrison 8);

- critical reflection: examining “the ethical and political dimensions of educational goals and the consensus about their ends” (Harrison 8).

While each level is important, the second — practical reflection — is what draws me to blog this New Year.

As I have worked with colleagues in interpreting their student evaluation data from the IDEA Center Student Evaluations instrument we use at Augustana, one of the matters we discuss is the selection of learning objectives that is central to the process. IDEA SRIs focus on student reports of progress on specific learning objectives selected as “essential” or “important” by the instructor. So, the instructor’s selection of priority objectives is obviously crucial. There are a couple of areas in the summary report to which I draw their attention: the reported progress on their selected objectives, of course, and also the raw data on objectives they did not select. If the scores on selected objectives is lower than expected, and/or the scores on unselected objectives is higher, at least one important question for practical reflection arises: Are the objectives you’ve selected really the focus of your teaching practice? Or is there a disconnect between your assumptions about teaching goals and your actual practice in the classroom? For instance, you may hold firmly to the notion that Objective #8, “developing skill in expressing oneself orally or in writing,” is important to your class. But do you actually spend time and energy instructing in this skill area in the class? Do your assignments clearly reflect and articulate that learning objective? If not, there may be a disconnect between what you believe or intend in teaching and your actual action in the classroom.

These three components of teaching practice — beliefs, intentions, and actions — are at the heart of the Teaching Perspectives Inventory (TPI), a free self-assessment instrument developed by Daniel D. Pratt and Associates based on extensive research into teaching beliefs, intentions and actions. The TPI is a 45-item survey that analyzes these three dimensions across five key teaching perspectives:

- transmission: “Effective teaching requires a substantial commitment to the content or subject matter”;

- apprenticeship: “Effective teaching is a process of socializing students into new behavioral norms and ways of working”;

- developmental: “Effective teaching must be planned and conducted ‘from the learner’s point of view'”;

- nurturing: “Effective teaching assumes that long-term, hard, persistent effort to achieve comes from the heart, not the head”;

- social reform: “Effective teaching seeks to change society in substantive ways” (Pratt and Collins 2001-2014).

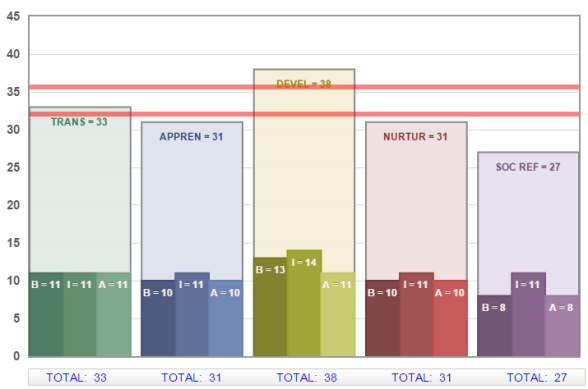

Any teacher will have varying levels of all five perspectives; some will be dominant, some recessive, and the levels may well change over time based on changes in knowledge, experience… and reflection! I took the TPI last fall — here’s how it shook out:

Developmental teaching reached above the upper line, indicating a dominant perspective. Apprenticeship, Nurturing, and Social Reform all fall below the lower line, indicating recessive perspectives. Overall, the results in the 30s suggest that these perspectives are held moderately. The emphasis on developmental teaching makes sense to me, although I note a bit of a disconnect between my intentions and my actions — something I’ve been pondering about my practice since I took this survey. I was a bit surprised that the three recessive perspectives were at these levels, considering the emphasis on disciplinary analysis of communication as political and social agency that I (think I?) stress in my classes. More fodder for reflection!

The TPI doesn’t assume that some perspectives are “better” than others. And it’s not a perfect instrument, to be sure. Rather, the results provide one lens for practical reflection: what assumptions about teaching drive your practice at a given time? And is there any disconnect between what you believe, what you intend, and/or how you act as a teacher?

So, as we move into 2015, let’s take the opportunity to reflect on the work we do, and resolve to be more reflective practitioners in order to match our actions to our intentions and serve our students well.

For more resources on reflective practice, check out the following:

- Stephen Brookfield, “The Getting of Wisdom: What Critically Reflective Teaching is and Why It’s Important” (from Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, Jossey-Bass, 1995)

- Karen F. Osterman and Robert B. Kottkamp, Reflective Practice for Educators: Improving Schooling Through Professional Development (Corwin Press, 1993)

- Sue Clegg, Jon Tan & Saeideh Saeidi, “Reflecting or Acting? Reflective Practice and Continuing Professional Development in Higher Education,” Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 3.1, 2002

Happy New Year!

Work Cited

Harrison, Jennifer. “Professional Development and the Reflective Practitioner.” In Sue Dymoke and Jennifer Harrison (Eds.), Reflective Teaching and Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008. 7-44. Print.